Rhawn Gabriel Joseph, Ph.D.

BrainMind.com

Hans was born in Berlin Germany early in this century and long amazed the local citizens with his ability to rapidly perform mathematical calculations. It was not the difficulty of the problems which was so astounding but the fact that Hans was a horse. For example, after a math problem was written on a blackboard, Hans would count out the answer by tapping his left forefoot to indicate 10, 20, 30, and so on, and with his right forefoot to indicate 1-9. In this way he was able to indicate if the answer were 17, 24 or whatever.

Trickery was ruled out because Clever Hans could solve the problems even when his owner was out of sight. However, when the owner and the audience were not shown the problem or the answer, Hans suddenly lost his amazing prowess. This is because the audience tended as a body to move forward as they watched Hans feet and would signal him via their movements as to how to respond. For example, they would tense as he approached the correct answer and would then move their heads when he reached it, signaling him to stop. When he did as their subtle body language suggested he was rewarded by a nice treat. Hence, it was well worth his while to act on their unconscious bidding.

If a horse can detect unconscious, seemingly unintentional body signals made by humans and then determine what they mean so as to act on them, then why not humans? The fact is, humans are also keenly attuned to receiving as well as transmitting similar body signals 1. However, at a conscious level this non-verbal form of language when subtle does not make a significant impression. Nevertheless, at an unconscious level a sometimes wholly unintentional form of communication take place with behavior being correspondingly affected.

Although body language may contradict or express views and attitudes that are not consciously intended, often these cues provide multiple layers of meaning and significance to what is being produced verbally as well. Sometimes, in fact, nothing need be said as the language of the body says it all.

Sara and Lisa were talking animatedly as they crossed the campus quad when Jesse waved to them and began strolling their way. Immediately Lisa hunched up her shoulders and clasped her books in front of her chest. Sara, however, threw her shoulders back and lifted up her chin, a pleased smile on her face.

Jesse strolled up confidently and standing with legs slightly spread apart grabbed hold of his belt buckle and knowing that Sara was watching him allowed his eyes to wander boldly up and down her body. Sara laughed, rolled her eyes and with one hand absently played with her necklace. Lisa, meanwhile, remained hunched over, arms crossed close to her chest, her eyes on the ground. Jesse bent down and picked up a twig and then stuck it between his lips. Giving Sara a wicked smile, he leaned close, and taking it in hand pretended to inspect her necklace.

Lisa took a step back, whereas Sara held her ground, smiled back and licked her lips very slightly with a darting movement of her tongue. Letting go of the necklace he again took hold of his belt and then suddenly with his other hand tapped her shoulder with the twig. Sara laughed, slugged him lightly on the shoulder, then brushed her hair away from her face with a sweep of her hand and arm which caused her breasts to jut out promisingly. However, although Jesse tended to wave his arms about and to keep invading her space by touching her, she held her ground, sometimes leaning close, sometimes leaning back, and only occasionally touching him in return.

Nevertheless, for the next ten minutes, whenever Jess said something funny, boisterous or crude, she would roll her eyes, bat her eye lashes, and pucker up her lips and then smile or laugh. Occasionally she reached out and hit his arm. Lisa, however, her body still in the same cramped position had taken hold of the edge of her sweater and absently played with it.

SEX DIFFERENCES IN BODY LANGUAGE

Some young girls learn to carry their bodies in a provocative manner so that their developing breasts are proudly displayed. Young males often tend to stand with a wider base and to make gestures toward their pockets (or rather genitals?) 2. Nevertheless, be it male or female, their movements and posture speak volumes as to their attitude, self-confidence, and even hidden desires. For example, some, like Lisa, will hunch up so as to hide themselves or absently cover select regions of their body as if they were a source of embarrassment.

It is clear that the Sara feels good about herself, whereas by her body language we know Lisa has a troubled self-concept and is insecure about her self and her body. Moreover, although we do not know what was said, it certainly seems that Sara and Jesse are very attracted to one another. Jesse almost seems aggressively interested due to his willingness to repeatedly invade Sara's personal space.

Males in general, however, are much more likely to invade the space of others and to gestulate more away from the body. They thus tend to take up more space when sitting or standing as their arms and legs are more likely to be extended out and as they tend to move around more when they sit or stand. Women tend to keep their arms and legs closer together and to move about less. Females also tend to gesture toward their body and to engage in more self touching 3. In fact, when it comes to self-touching, both sexes are more likely to use the left hand, whereas the right is more frequently used for gesturing during speech 4. However, when women touch, it is likely to be much more gentle and much more caressing than a male who tends to use much more force.

In general, men touch both females and males more than women touch males. Women and girls are much more likely to hug, touch, hold hands, and make repeated and long lasting physical contact with one another but are quite reticent to behave in the same manner with a man unless they are lovers or family. Indeed, even in regard to simple touching, a woman is almost four times more likely to be touched by a man than vice versa. However, when men touch men this contact is usually very brief and consists of friendly slaps, slugs, punches, and pushes 5. Unfortunately, due to female reticence and the male proclivity for repeatedly making brief physical contact, when a female is a recipient of such attention there is some likelihood that it may be misinterpreted as threatening or sexual even when it is not.

Females also begin smiling soon after birth and thus smile at an ealier age than males. Females also smile on average about 30% more than males and are far more likely to maintain sustained and direct eye contact with a woman than a man is with a man 6. Males often perceive direct eye contact as a threat (which is true for most primates and many other male animals) and are thus less willing to provide it 7.

When females make eye contact this is also much more likely to be coupled with appeasement facial expressions such as smiling and head bowing or nods 8. That is, the smile serves so as to reduce social tension and threat. Again, these are common appeasement gestures for our cousins, the apes, as well as for wolves, dogs, and similar creatures.

Insofar as a smile may be mistaken for appeasement, men are less likely to employ a smile even when making direct eye contact. This reluctance regarding eye contact is even evident during infancy and is even suggested in the types of toys boys vs girls prefer to play with 9. That is, females are more drawn to toys that have an easily identifiable and human-like face, such as teddy bears and dolls, whereas boys like toy guns, trucks, blocks, hammers and so on, including actions figures where their essential humanness are deemphasized.

MALE AND FEMALE BRAINS

These sex differences are in part a function of differences in hormones and the structure of the male versus female limbic system. Specifically, the pattern and density of growth and interconnections within the hypothalamus and the amygdala of male and female brains, are sexually dissimilar 10. This is a consequence of genetic programming and the presence or absence of the male hormone, testosterone, within the first few fetal months of life. Those whose baby brains are bathed in testosterone subsequently develop the male pattern of neural growth. This is important for the female limbic system is called upon to perform many functions, such as involving the monthly menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and lactation, that male brains simply are not wired to accomplish. Hence, their patterns of limbic neural growth and interconnections reflect these different concerns.

As noted, the ability to experience pleasure or aversion is a function of the limbic system, the hypothalamus in particular. Hence, one consequence of this difference in limbic structure and function is that males vs females experience and express pleasure in response to different stimuli, thoughts, and acts. For example, the hypothalamus and amygdala generate feelings of pleasure when males act aggressively and when they kill.

In contrast, the female limbic system is wired so that they experience positive sensations and feelings when presented with creatures that are helpless and dependent, such as their own smiling babies. Thus females are more nurturing and less aggressive, which is also a function of males but not females being in possession of one of the most dangerous chemical substances found in nature, testosterone. It is testosterone which induces the male pattern of neural development and which later in life acts to promote aggressive and even murderous behavior, a trait that is not to the advantage of the individual or the species if possessed equally by females.

Only females who feel compassion and tenderness, who love (or can at least tolerate) the sensation of dependency and who can lovingly nurture her baby even as it is biting and gnawing on her sore body, or waking her repeatedly night after night, make good mothers. This nurturing tolerance comes naturally to them as their brains are wired so as to generate feelings of pleasure in response to the helpless and loving dependency of her baby. The female must be able to suppress the desire to strike out or to kill, for otherwise her kind would soon be weeded out.

In contrast, over the course of evolutionary history, males who were unable to suppress feelings of compassion and nurturance were also weeded out. They would have made very poor hunters, for when confronted by those dear sweet Bambi eyes on some small or helpless creatures, they would have felt compassion and more often than not, might have let it go. As such, except for the meat brought home by their mate, their diet would probably have been largely vegetarian.

Males who derived little pleasure from killing and instead chose other means of procuring food would probably also have had trouble finding breeding partners due to the higher premium placed on men who brought home meat from the kill. Meat which they would use to share and barter, adding to their stature in the bargain.

In the ancient hunter gatherer societies, successful hunters probably had many wives and even more extramarital affairs, and thus many, many children. Hence, those who experienced pleasure when killing and those with limbic systems wired differently from the female so as to generate positive feelings in this regard, may well have had some advantage over those less inclined. Hence, similar to those females who respond with love and compassion to those helpless and dependent, these ancient hunter killers, were more likely to have thrived, survived and passed on these limbic traits to their forebears.

CONTRADICTORY BODY LANGUAGE & SEX

Most people reveal a great deal of personal information inadvertently via body and facial cues, posture, eye contact, hand gestures, inflectional vocal nuances and their clothing. However, because this non-verbal form of communication was developed long before the advent of consciousness or even the evolution of the ancient hominids that gave rise to man and woman, most of it continues to occur and make impressions at an unconscious level. As such, it continues to influence human behavior sometimes in a manner that neither the receiver nor the sender intends, particularly if a contradictory message is being conveyed through a different modality, e.g. speech. For example, the woman who says "no," but with her body and eyes says "yes."

In fact, females of many species provide contradictory signals to males regarding sexual availability, one form of which is flirting 11. Moreover, it is a pronounced tendency of sexually receptive females (e.g. lizards, birds, dogs) to make her availability obvious and to then run away only to be actively pursued by one or several sex crazed males. Among these species, it is only the dominant male who does not accept these seemingly contradictory messages who is able to successfully breed. On the other hand, among some animals, such as rabbits, young males who fail to heed the otherwise receptive female's adamant disinclination for sex, end up as castrates, for she is likely to bite off his testicles. Modern human males need to be similarly wary and may be best advised to interpret "no" as meaning exactly that.

BODY LANGUAGE & INNER NATURES

Gesture is not just an adjunct to speech, for humans are able to converse quite fluently through the motions and movement of their body even in the absence of the spoken word 12. The language of the body is a veritable treasure trove of information as to a persons intentions, desires, fears, emotional state, and self-confidence. The manner in which it is employed can greatly aid or diminish one's ability to successfully navigate the stream of socializing that makes up our every day world be it business, love, or political or sexual conquest.

Through gesture and facial expression, emphasis, context, elaboration, and depth is added to the content of all that is uttered and can open our eyes to possibilities not conveyed by speech. This is because gesture is a completely different and separate language by which man and animal speak through their movements.

BODY LANGUAGE & FASHION

Our human ancestors were no doubt at one time covered with a dense, thick coat of hair and ran about naked for much of the season. As such many social signals could be conveyed via changes in one's coat, such as by one's hair standing on end or puffing out such as in displays of fear or anger. Signals could also be transmitted via facial and hand gesture and manipulation or exposure of the genitals, such as an erect penis or a swollen red vagina.

With the loss of much of man and woman's hair and the consequent covering up of the genitals, dress and other adornments took on considerable importance in making a social statement and thus body language. Hence, body language can be conveyed through clothing and in this regard, clothing can reveal as much as it hides.

A woman wearing a tight skirt, cut short, with high heels and a blouse that reveals a good part of her cleavage is definitely sending a signal which reeks of sexuality regardless of what her claims to the otherwise might be. A man who shows up at an informal gathering wearing a suit and who refuses to relinquish his coat may be perceived as quite stuffy, conservative and reserved. Certainly not the life of the party. Conversely, the man who shows up at a formal party wearing sneakers, T-shirt, and blue jeans may be perceived as inappropriately casual, scruffy, and rebellious if not rude.

Attitudes and feelings conveyed via adornments, decorations and dress, in fact have biological underpinnings. Many mammals, birds, fish and reptiles use body decorations as a means of signaling status and intention, particularly males as their coloration and coat also serve to attract willing female sex partners 13. In this regard, males in general tend to be much bigger, more muscular, colorful and sport the more luxurious coat of hair, whereas females are generally quite drab in appearance. Females are nevertheless affected and attracted by these signals, and are more likely to mate with those who are the most colorful, biggest, and so on.

Indeed, due to this tremendous power coloration and body adornments exert over females in general, human females eagerly apply numerous cosmetics and dyes to their body and hair, and dress in a variety of colors and fashions, and these interests consume a considerable amount of their time and attention. The human female remains biologically predisposed to respond to such cues, but unlike females of other species, she is no longer dependent on the male to provide her with this stimulation. She can apply it herself and instead responds to the dress and fashion of other women.

This is why many women indicate that they do not dress for men, but for other women, and why females are concerned with the dress and cosmetics worn by other females 14. Indeed, in contrast to many Westernized women who may sport and own dozens if not hundreds of outfits and shoes, many males are content to dress the same from day to day.

For a long period of human history, the clothes one wore, the decorations that adorned one's body also conveyed volumes as to one's character and capability. The ancients would clothe themselves in the skins of animals and would wear their teeth, claws, feathers all of which indicated one's strength, status, and accomplishment. Hence, if you wore the teeth of a lion, bear or a tiger, you must be pretty ferocious. If your hair was decorated with the feathers of an Eagle one was not only an agile hunter but wise and cunning. Moreover, not just the material, but the manner in which it had been fashioned spoke volumes as to the talents of the seamstress. One was clothed in their conquests and accomplishments, or those of their mate, and was able to parade his or her abilities and say to all who he is and what he is capable of.

Sadly, almost ridiculously so, among modern humans the nature and meaning of these displays has completely broken down. Now all one needs to do is buy certain mass marketed clothes and assume an identity via identification. In this manner one may look like "cool" or "bad" or like a rock star, cowboy, lumber jack, fashion model, movie star, gang member, or worse, one can parade the name of some fashion designer, like a brand on their butt or chest. Many modern westernized humans have become walking billboards advertising their own psychic impoverishment, or, in the case of children, that of their parents.

BEFORE BABYLON: THE UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE

Originally (and beginning in prehistoric, preverbal times) infants and adults communicated many of their likes, dislikes, desires, and needs with little reliance on words but instead used gestures and facial expressions which were innate and natural in origin and understood across cultures 15. Indeed, children are said to employ over 150 natural gestures and signs, many of which they unlearn or modify as they grow older 16.

Due to their innate origins, many forms of body language serve as a silent, non-verbal means of complex signaling that are universally understood. Regardless of culture, people smile the same and a smile accompanied by raising of the eyebrows and a nod of the head is a universal greeting gesture 17. A similar gesture passed between men and women is often seen as flirtatious. Conversely, the balled fist, flexed arm, furrowed brow, open mouthed or tight lipped expression is an indication of anger be it monkey, ape or human. Of course, not all signs are universal.

Because many natural signs are a manifestation of the hardware of the brain and have little or nothing to do with learning, we see that even children who are born blind and deaf still smile and emit appropriate sounds when happy. Similarly, when sad or upset they will frown, stamp their feet, and clench their fists. Severely retarded children with no language capabilities who are extremely limited in their ability to learn or even mimic what they see, can still laugh, smile, weep, and show signs of rage by yelling and screaming and stamping their feet in anger. Chimpanzees and gorillas respond likewise when angry, including baring the teeth in an open mouth posture of rage.

Many complex depictive gestures which are employed predominantly by adult human beings, have common biological roots as they are related to the functioning of the body. It is these gestures which are more or less expressed similarly or have the same meaning across cultures. For example, touching the ear with a single finger to indicate that one does not understand or hear what is being said, holding one's nose and wrinkling one's face and mouth may indicate the presence of a disagreeable odor, rubbing the tummy may indicate hunger or a stomach ache, touching one's temple or forehead with the index finger may indicate thinking, turning the same finger in a cork screw fashion may indicate craziness (a "mixed up" mind), and slicing a finger across the throat may indicate an upcoming death by decapitation, or the need for the opposing party to shut up.

Natural (biologically rooted) signs are first and foremost rooted in emotional displays and thus have common limbic origins 18. However, many gestures, although originally natural and seemingly shaped by innate physical and biological predispositions, also come to be shaped by the cultural and social environment in which one is raised. Natural signs and gestures, like spoken language, are subject to modification, and abbreviation or they become stylized to various degrees as they become part of a common currency of exchange 19. For example, in a military culture the open (empty, non-threatening) hand above the eyes (which decreases the threating nature of direct visual contact) has become a military salute.

Just as dialects and languages have evolved from common roots, many gestures have also differentially evolved so as to form distinct gestural languages as well. Nevertheless, many gestures and facial expressions such as feelings of puzzlement, doubt, contempt, anxiety, insecurity, or haughtiness are easily understood between most cultures 20. Many gestures in fact circumvent language and illuminate or make unnecessary an exchange of dialogue; e.g. blowing a kiss, shaking hands, kissing on the cheek. In fact, certain gestures convey meaning that are very hard to put into words, such as demonstrating versus explaining how a corkscrew works and what it is shaped like. In many ways, spoken language, being a more recent acquisition, still lags behind gesture and specific body movements as a form of intellectual and social currency. In many situations it is clearly not as efficient as gesture for communicating.

NATURAL SIGNS AND GESTURES

Signs and gestures, albeit natural and innate, are not limited to emotional exclamations but can impart precise information about ones experiences, intentions, hopes, and desires. This form of communication is possible even among individuals raised thousands of miles away who speak completely different dialects, or who cannot speak at all having been born deaf.

For example, MacDonald Critchley, described a number of "deaf and dumb" children from France, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Italy with no formal training in sign language or lip reading who were temporarily gathered together at a special school for a weekend 21. Critchley noted that within an hour or two they were all communicating freely with each other, and understanding each other almost completely via the use of natural signs and facial expressions alone.

Similarly, among the American Indians, although over 65 linguistic families were still in existence by the mid 1800s, even those who lived thousands of miles away and spoke a completely different dialect had little difficulty communicating via the use of natural and imitative signs. For example, to indicate snow or rain they might hold their palms up and then slowly wiggle their fingers as they dropped their hands. To indicate cold, they might clench both fists then fold then against the chest followed by a trembling motion. Via gesture and the use of natural and immitative signs complete and detailed conversations could be held between individuals who knew nothing of the other's native tongue.

Nevertheless, unlike spoken language, this natural gestural language of signs does not possess the "deep structure" grammatical organization that supposedly typifies spoken language. This is true if it is employed by the deaf or by the various tribes of American Indians, all of whom are able to communicate quite effectively via the use of these aggrammatical natural signs. In contrast, formal gestural systems such as American Sign Language are grammatically complex 22. Being more complex in turn makes possible greater complexity and precision in communicating and inquiring and thus greatly expands upon the horizons of what is more natural. They in fact, complement one another.

THE ORIGIN & EVOLUTION OF GESTURES

Gestures are the result of tendencies to shape naturally occurring behavior patterns so as to convey and represent ones feelings and internal emotional and motivational states 23. It is in this manner that body movement becomes infused with meaning. Similarly, ontogenetically and phylogenetically, the earliest movements, be they of a modern infant or a primitive mammal scurrying about in the darkness of the jungle, are representative of diffuse and rather global feelings and emotions such as pleasure, rage, fear, or they are produced as a product of self-stimulation or reflex. Although expressive of a feeling or motive, the early movements and gestures of an infant do not consist of signs but occur within certain contexts which gives them meaning. That is, a smile is just a smile and in the absence of context is of limited meaning. The same could be said of an adult smile which may convey contempt, anger, disbelief, as well as happiness.

Infantile movements themselves are initially very global, sprawling, and unfocused, involving the entire body musculature or at a minimum body parts irrelevant to the action being explored. It is only as the child ages that movements become more distinct and specific such that bodily gestures eventually become increasingly localized to the arms, hands and face 24. As the infant and its nervous system mature it increasingly adds to its repertoire of movement patterns. This in turn can be increasingly modified for the purposes of interacting with the environment and grasping some desired object. Many movements and gestures in fact, come to be associated with the use of certain objects, tools, toys, and utensils.

With the rapid differentiation of the limbic system and the right brain mental system, not just movements but emotions come to be more refined, specific, and less global as the child ages 25. Now specific emotional states are experienced and these in turn come to be expressed via specific movements as the infant screams, babbles, cries or coos. Soon the lips and vocal tract also comes to be specifically shaped so that certain words are formed.

Similarly, with the maturation of the neocortical motor areas in the frontal lobes, movements become more precise. From this point on these and related motor programs begin to receive a temporal-sequential stamp as they are acquired and repeated endlessly. Finally these movements become stylized and habitual as they are repeatedly relied upon to perform certain tasks.

When pretending to perform a certain task or using some imaginary tool or object, the behavior is then recognized as mimicry and pantomime, a form of gesture that lies intermediate between natural gestures and depictive gestures including what is recognized as sign language 26.

Over time there is increasing differentiation such that innate and imitative gestures become more and more spatially and temporally distinct from that which it is representing and thus less and less naturalistic. That is, gestures and movements become increasingly distinct from their biological roots.

THE ONTOGENY OF IMITATIVE GESTURES

Human beings sometimes use imitative gestures when painting and drawing, when pretending, playing, mocking or story telling, as well as when attempting to describe. This is a capacity that is not only informative and amusing, but which is also fairly unique to apes, monkeys and humans. Children begin to make imitative moments almost from the time of infancy 29. However, because of their poor motor control they may mimic with the wrong muscle groups. For example, they may open and close their mouth when mommy is blinking her eyes. To merely imitate, however, communicates very little and may in fact communicate nothing at all and serve only to reflect.

True depictive movements and gestures do not begin to appear until between the ages of 2-3. At this age children can depict by gesture size, form, and then later, objects, animals, and activities 27. Although this too is made possible via imitation, it is imitation meant to depict and to inform. For instance, they may depict a flickering light bulb by rapidly blinking their eyes or they may make stirring motions with their finger to indicate a spoon, or they may outline the shape of the item or object via hand movements in the air.

As children increasingly refine their ability to imitate particular patterns of movements they are also able increasingly to separate the signs and gestures they use from the objects they are trying to depict. In the early stages of imitation they pretend to drink out of a glass that is full. Then, as they age, they pretend to drink out of an empty glass, then without a glass while making smacking and swallowing motions.

Similarly, consider the use of a scissors. One can depict the use of scissors by bumping her thumb and forefinger together as if she were holding and cutting with it. Or she can imitate the scissors by taking the index and middle finger and snapping them together as if cutting. However, as pointed out by Werner and Kaplan, in the latter instance, the movements are functional and more reality oriented so as to serve the purpose of imitating events and activities of every day life 28.

Initially, however, imitative acts involve movements which mimic the actual use of objects, with the exception that part of the body, the hand or arm, is substituted for the missing object, such as in pretending that the hand is a hammer instead of pretending to hold a hammer. In all other respects, these imitative acts involve the repetition of the exact motor sequence which makes up the natural act. Similarly, symbolic movement and gestures evolve from imitative acts.

One might supposed that the ontogeny of symbol acquisition has followed a similar path from ape to human during its long evolutionary journey. In fact, when we consider the most recently acquired and advanced form of making depictive gestures, i.e. writing, it is clear that its development followed a similar evolutionary course being preceded by drawing. This appears to be true for modern day children as well as for the evolution of pictorial and written verbal thought. Writing evolves from picture making 29.

GESTURE & CHILDREN'S SPEECH

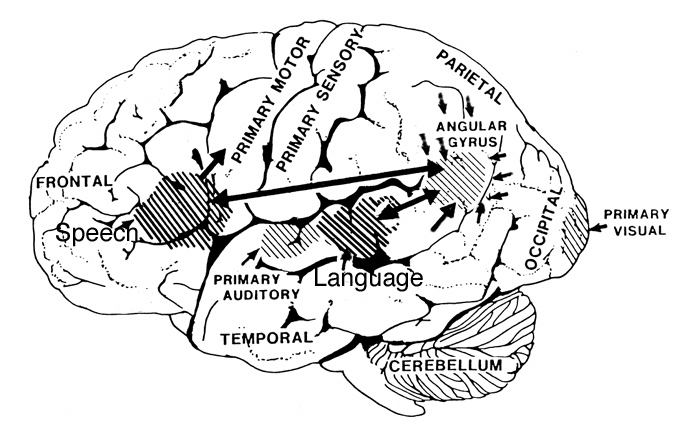

The use of gesture expands in accordance with refinements in motor control and seems somewhat independent of speech. Indeed gesture is organized much differently from speech and retains its natural, non-grammatical organization and is not always employed in coordination with what is being said. In part this is a function of speech being mediated by the temporal and frontal lobes, and gesture being comprehended by the visual areas within the parietal lobe 30. Different brain regions mediate different language systems. However, these differences in expressions are also a function of the different rates of maturation for different regions of the child's brain, such as those controlling speech versus gestures.

For example, a 4 year old will pantomime the use of a hammer before describing it. A 10 year old will pantomime while he is explaining, whereas a 14 year old will gesture selectively and employ gestures only in relationship to certain words so that the two systems of communication are coordinated 31. Hence, with increasing age, gesture and speech become more closely associated and organized together, and gesture becomes more grammatical as well.

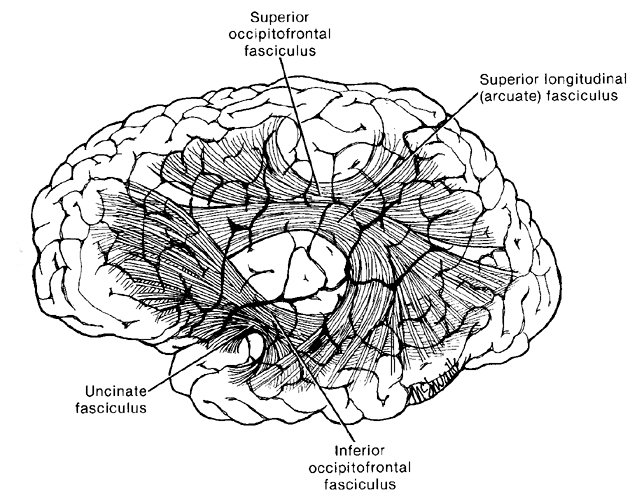

this developmental sequence is neurologically determined and further indicates that speech and gesture are in fact different communication systems that are interlinked but which also rely on different brain tissue for their expression and comprehension 32. The progression of gestures as they are modified from natural and innate to imitative, to depictive and temporal-sequential and symbolic, are dependent on the maturation of the parietal lobe, the inferior regions in particular which sits at the juncture of the visual, auditory and tactual regions of the brain. The inferior parietal lobe is one of the last neocortical regions to functionally mature, taking over ten years 33.

GESTURE, SIGN LANGUAGE & THE INFERIOR PARIETAL LOBE

The limbic system acts to analyze sensory and tactual information in regard to its potential emotional and motivational significance. It is via the neocortex of the parietal lobe that one comes to analyze the external sensory-physical properties of various objects and stimuli and to associate them together in the form of ideas. It is also the seven layered neocortex which enables us to achieve knowledge of the physical world as well as discern it's potential motivational and intellectual attributes. The neocortex, however, does not replace the old cortical nuclei. Rather it acts semi-independently to analyze the emotional as well as those non-emotional characteristics of the world which the limbic system is not concerned with. It is in this manner that we come to know, and know that we know.

All physical and tactual sensations are transmitted to the primary receiving area for somasthesis, which is located within the neocortex of the parietal lobe. The parietal lobe is sensitive and responsive to tactual stimuli regardless of where on the body it is applied. In fact, via the reception of these signals from the sensory surface of the body, the entire body surface comes to be spatially represented in the sensory neocortex.

When part of the body is touched or stimulated, cells in the primary receiving area fire. Conversely, if select regions of the primary receiving area were electrically or abnormally stimulated, the person would experience a tactual sensation occurring on a circumscribed portion of the body; i.e. that body part which projects via a series of cellular relays to the neocortical cells being stimulated. Electrical stimulation of these neocortical cells can elicit well localized sensations on the opposite half of the body such as numbness, pressure, tingling, itching, tickling and warmth.

The parietal lobes are responsive to a variety of divergent stimuli. This includes tactual, kinesthetic, and proprioceptive information, sensations regarding movement, hand position, objects within grasping distance, audition, eye movement, as well as complex and motivationally significant visual stimuli 34. Moreover, the parietal lobe contains neurons which are visually sensitive to events which occur in the periphery and the lower visual field; regions where the hands and feet are most likely to be viewed. Some neurons in this area also become highly active when an individual reaches for some item, whereas other fire when the item is grasped. These latter neurons are referred to as hand-manipulation cells 35.

Analysis and guidance of the body's position and movement in visual space, the hand in particular, is a primary concern of the parietal lobe. That is, it guides the movement of the arms and hands as they move through space regardless of purpose or object of desire. In this regard it mediates eye-hand coordination. The parietal lobe, however, does not keep its "eye" on the ball (or the net, hoop, hole or whatever) but on the hands and arms. It does not receive visual information from the fovea of the retina of the eye. Rather it has only black and white peripheral vision. Again, these are the visual areas where the hands and legs are most likely to be viewed and is this regard the parietal lobes are responsible for comprehending the significance and meaning of hand movement and gesture as well as coordinating the feet as a person runs, dances, or walks about in space.

It is via the perceptual activity of the parietal lobule that we come to know that a wave of the hand means "come" or "goodbye," or that someone has balled up their fist and may punch us in the nose. In their most refined form these movements and gestures are expressed in the form of sign languages including the writing in pictures and in script, all of which is completely dependent on feedback from touch and which is made possible via select regions within the parietal lobe, specifically, the inferior parietal lobule, a structure which is largely unique to human beings.

By receiving visual as well as information regarding the limbs of the body, the parietal lobe, especially that of the right half of the brain, enables us to run, jump, do summer salts and perform gymnastics, as well as guide and program the hands so that the skills of carpentry, bricklaying, drawing, painting, and other fine arts are made possible. It is also via the parietal lobe that complex skilled temporal-sequential tasks can be performed, such as preparing a pot of coffee or brushing one's teeth 36.

Through its control over body and limb movements, the parietal lobe over the course of evolution, has become increasingly involved in gestural communication. Indeed, this brain area in fact mediates the ability to perform not only simple and "natural" signs, but complex, grammatically based, gestural sign systems such as American Sign Language (ASL). In fact, if this area of the brain were injured, the ability to comprehend ASL as well as natural signs would be compromised, although a person could still speak and understand what was said to him 37. Speaking and verbal comprehension are a product of the left frontal and temporal lobe respectively.

COMMUNICATING VIA SIGNS

There once was a girl who could neither hear, nor speak, or write, nor communicate by signs. It was only through a long terrible struggle that occurred completely within her world of touch that the mind of Helen Keller's was suddenly illuminated by the world of language.

"Earlier in the day we had a tussle over the words "m-u-g" and "w-a-t-e-r." Miss Sullivan had tried to impress it upon me that "m-u-g" is mug and that "w-a-t-e-r" is water, but I persisted in confounding the two. I became impatient of her repeated attempts, and seizing my new doll, I dashed it upon the floor. I was keenly delighted when I felt the fragments at my feet. I had not loved the doll. In the still, dark world in which I lived there was no strong sentiment or tenderness....

We walked down the path to the well-house. Someone was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten--a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, and set it free!...

I left the well-house eager to learn. Everything had a name, and each name gave birth to a new thought. As we returned every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life... I saw everything with the strange new sight that had come to me. On entering the door I remembered the doll... and picked up the pieces. Then my eyes filled with tears; for I realized what I had done, and for the first time I felt repentance and sorrow.

-Hellen Keller 38

Humans have employed gestures and movements to mime and dance, to pantomime and to convey the symbolic, the sublime, the abstract, the mythical, magical, and mystical (which is why many religions utilize symbolic gestures in their rituals and liturgies) long before the development of written or complex grammatical spoken language. Gesture may have not only been a forerunner to spoken language, but provided the context in which it could develop.

Because gesture is a precursor to the development of speech, it is commonly employed by those without speech but who possess highly developed social brains. Apes, monkeys, dogs, wolves and other animals are able to gesture through eye and body movement, and facial expression and are even able to mime and dance 39. Even unrelated species make several of the same gestures which essentially have the same meaning; a puppy will sometimes naturally raise it's paw as if to shake and show friendliness when confronted appropriately and apes and monkeys commonly make hand to hand contact as a signal of appeasement and friendliness.

Given that so many postures, facial expressions, and arm and hand movements are understandable not only between cultures but between animals and man, certainly raises the possibility that the neurological foundations of gesture are similar between species. These similarities could also be due to the possibility that they were subject to similar environmental pressures in order to survive.

This is why, perhaps, that dogs and humans both feel guilt, shame, depression, anger, jealousy, and love. Both share a very similar limbic system, have similar brains, and have lived quite comfortably together for at least 10,000 years.

However, dogs don't rhyme, curse and use foul language or put much effort into describing their world though they are certainly not lacking in curiosity. In contrast, as has been shown with the chimpanzees Washoe and Lucy, Koko the gorilla, and other apes, these capacities are not limited to human beings as these primates possess similar aptitudes.

How do we know this? First via the extensive observations of Jane Goodall on wild chimpanzees living in the Gombe field reserve in Africa complied over a 30 year time period, and through the efforts of the Gardners of the University of Nevada, Francine Patterson of Stanford, and many other scientists 40. Indeed, the Gardners and Dr. Patterson were able to teach these creatures American Sign Language and were thus able to "talk" with them.

AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE & THE ACQUISITION OF TEMPORAL-SPATIAL GRAMMAR

American Sign Language (ASL) is a complex gestural language utilized by the deaf as their primary means of communicating with others. It is composed of natural as well as artificial signs which have been forged into a grammatical gestural language that is thus visual and verbal, but not auditory. However, unlike natural signs, ASL is a bit cumbersome and it takes about twice as long to indicate a word via gesture as to say it out loud.

In general, there are two structural levels to signing 41. The first level includes the rules which govern the relations between signs within sentences. The second level is concerned with the internal structure of the lexical units.

ASL makes use of space patterns and the contours of movement; i.e. hand shape, movement, and spatial location which is actively manipulated in regard to indicating syntax, nominals and verbs. For instance, nominals are assigned locations in the horizontal plane, and verb signs move among these spatial loci so as to indicate the grammatical relations between the subject and object. Moreover, the same hand shape presented in different motions or at different spatial locations, conveys different grammatical and semantic information.

Although highly grammatical and dependent on temporal contrasts, ASL is very sensitive to spatial contrasts. However, these spatial contrasts are heavily dependent on verbal described relationships such as "right" vs "left", "up" vs "down." Space and movement become subordinate to verbal labels and coordinates. Unlike gestures, be they cultural or natural in origin, ASL employs linguistic, temporal sequential, and visual referents, and thus represents a multidimensional as well as grammatical means of complex communication via movement.

THE INFERIOR PARIETAL LOBULE & TEMPORAL SEQUENCING

To be capable of learning and producing this formalized system of gestural interrelationships considerable evolutionary adaptation and development in the parietal lobes was required. Some of this development occurred in the superior parietal lobe which is concerned with the movement of the hands and arms in visual space. However, with the evolution of parietal tissue at the juncture of the occipital (vision), temporal (auditory) and inferior frontal (motor) areas the development of a complex grammatical gestural language including the temporal sequencing of sound was made possible 42. The appearance of the angular gyrus of the inferior parietal lobule helped make possible the creation of human speech and all associated nuances of language, e.g. reading, writing and arithmetic.

Grammatical, denotative spoken language is in part a secondary acquisition which follows the development of the superior and inferior parietal regions and thus the ability to gesture in temporal sequences. Nevertheless, animals that cannot speak but who possess some of the same brain structures as humans are also able to learn and employ complex systems of gesturing and signing so as to communicate their own interests and desires.

Apes and humans are all blessed with well developed parietal lobes and limbic systems. Apes, however, possess only the first hint of what in humans is referred to as the angular gyrus which along with the marginal gyrus makes up the inferior parietal lobule. These neocortical structures are extremely important in the acquisition of language. Sitting at the junction where visual, auditory and tactual sensations are processed, they are able to integrate these different signals so that multiple categories can be assigned to a single sensation or idea 43.

Primates are able to make considerable use of their face, hands and arms for the purposes of gesturing and this has been made possible via the tremendous evolutionary development that has occurred in the parietal lobes. Thus the ability to gesture with the hands and arms as a means of communication is most developed in primates. Similarities in gestures and the brain, however, are also a function of both species being subject to similar evolutionary pressures early in their history, especially in regard to the development of the upper arm and hand, and the ability to grasp and manipulate objects. It is also for these reasons that humans and apes are in fact capable of acquiring and communicating via complex systems of gesturing, such as via ASL.

REFERENCES