Rhawn Gabriel Joseph, Ph.D.

BrainMind.com

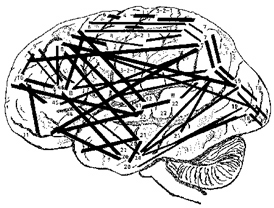

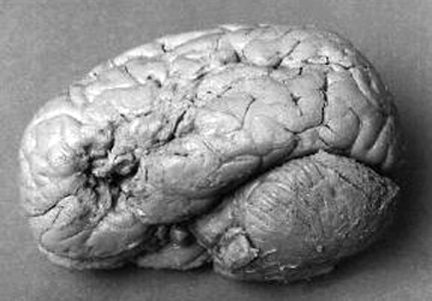

The frontal lobes serve as the "Senior Executive" of the brain and personality, acting to process, integrate, inhibit, assimilate, and remember perceptions and impulses received from the limbic system, striatum, temporal lobes, and neocortical sensory receiving areas,

Moreover, through the assimilation and fusion of perceptual, volitional, cognitive, and emotional processes, the frontal lobes engages in decision making and goal formation, modulates and shapes character and personality and directs attention, maintains concentration, and participates in information storage and memory retrieval.

Because of its widespread functional capabilities and interconnections, if damaged there can result excessive or diminished cortical and behavioral arousal, disintegration of personality and emotional functioning, difficulty planning or initiating activity, abnormal attention and ability to concentrate, severe apathy or euphoria, disinhibition and a reduced ability to monitor and control one's thoughts, speech, and actions, including loss of memory.

Moreover, frontal lobe abnormalities commonly result in major cognitive, perceptual, and emotional disturbances, such as schizophrenia, catatonia, mania, depression, obsessive compulsions, aphasia, confabulatory delusions, and the "frontal lobe personality."

Patients may also develop paralysis of the extremeties, or demonstrate severe unilateral neglect of visual-auditory space, or conversely, compulsively utilize tools or other objects, such that in the extreme the right or left hand may act completely independently of the "conscious" mind.

The reason for such a wide range of potential disturbance is that rather than a single pair of frontal lobes there are several "frontal" regions which differ in regard to embryology, phylogeny, cellular composition, functional specificity and interconnection and interactions with other brain areas. The frontal lobes are not a homologous tissue, and each frontal region is concerned with somewhat different as well as overlapping functions. Moreover, damage is rarely restricted to one specific frontal area but commonly disrupts adjoining "frontal" tissues as well. Hence, well localized, as well as a wide ranging spectrum of divergent neuropsychiatric, clinical abnormalities may be induced, sometimes simultaneously, depending on the nature, extent, laterality, and location of the disturbance.

FUNCTIONAL OVERVIEW:

The right and left frontal lobes appear to exert differing influences over arousal, attention, sexual, emotional, and memory functioning (Brewer, et al., 1998; Joseph, 2007a, 1988a, 2011a; Konishi et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 1998) including even humor appreciation (Shammi & Stuss, 2011).

Specifically, reduced speech output, Broca's aphasia, apathy, "blunted" schizophrenia and major depression are often associated with left lateral (and bilateral) frontal injuries (Bench et al., 2013; Benes, McSparren, and Bird, 1991; Buchsbaum et al. 1998; Carpenter et al. 1993; Casanova et al. 1992; Curtis et al. 1998; d'Elia and Perris 1973, Goodglass & Kaplan, 2011; Hillbom 1951; Perris 1974; Robinson and Downhill 2013; Sarno, 1998). Adults with PTSD also display reduced left frontal lobe activity (Rauch et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2007), whereas sadness can reduce right and bi-frontal activity (Mayberg et al., 2011), though in most instances depression is directly attributed to left frontal dysfunction (see below) and reduced left frontal activity as demonstrated through functional imaging (Bench et al., 2013). As per schizophrenia, it is noteworthy that lateral frontal gray matter reductions and decreased brain volume and activity have been repeatedly noted (Andreasen et al. 1990; Buchanan et al. 1998; Curtis et al. 1998).

By contrast, impulsiveness, confabulation, "motor mouth," grandiosity, and mania are often produced by right frontal (as well as bilateral) lesions (Bogousslavsky et al. 1988; Clark and Davison 1987; Cohen and Niska 1980; Cummings and Mendez 1984; Forrest 1982; Girgis 1971; Jack et al. 2003; Jamieson and Wells 1979; Joseph 2007a, 1988a, 2011a; Lishman 1973; Miller et al. 2007; Oppler 1950; Robinson and Downhill 2013; Rosenbaum and Berry 1975; Starkstein et al. 1987; Stern and Dancy 1942; Stuss and Benson 2007). Moreover, as the right frontal lobe is associated with the expression of emotional melodic speech injuries to this area can also produce pressured and/or confabulatory speech that may be melodically distorted.

THE FRONTAL LOBE PERSONALITY

With unilateral, bilateral, or even seemingly mild frontal lobe dysfunction patients may initially display an array of waxing and waning abnormalities including the "frontal lobe personality," i.e. tangentiality, childishness, impulsiveness, jocularity, grandiosity, irritability, increased sexuality, and manic excitement (Joseph, 1988a, 2011a; Lishman, 1973). Over fifty years of research and numerous case studies have consistently indicated that with significant frontal lobe pathology attentional functioning may become grossly comprised, behavior may become fragmented, and initiative, goal seeking, concern for consequences, planning skills, fantasy and imagination, and the general attitude toward the future may be lost.

The patient's range of interests may shrink, they may be unable to adapt to new situations or carry out complex, purposive, and goal directed activities, and lack insight, judgement, and common sense (Fuster 2007; Freeman and Watts 1942; Girgis 1971; Hacaen 1964; Joseph 2007a, 1988a, 2011a; Luria 1980; Passingham 1993; Petrie 1952; Stuss 1991; Stuss and Benson 2007). Conversely, when engaging in memory, planning, decision making, goal formation, and tasks requiring imagination, the frontal lobes become highly active--as demonstrated by functional imaging (Brewer et al., 1998; Passingham, 2007; Wagner et al., 1998; Dolan et al., 2007; Squire, et al,. 1992; Tulving et al., 2014; Kapur et al., 2013).

With massive trauma, stroke, neoplasm or surgical destruction (i.e. frontal lobotomy), patients may show a reduction in activity and take very long to achieve very little. They may be unconcerned about their appearance, their disabilities, and demonstrate little or no interest in self-care or the manner in which they dress, or even if their clothes are soiled or inappropriate (Bradford 1950; Broffman 1950; Freeman and Watts 1942; Petrie 1952; Strom-Olsen 1946; Stuss 1991; Stuss and Benson 2007; Tow 1955).

Although some patients demonstrate restlessness, impulsiveness, and flight of ideas, they may also tire easily, show careless work habits and a desire to get things over with quickly. As repeatedly documented following frontal lobotomy, they may immediately develop a tendency to lie in bed unless forcibly removed (Broffman 1950; Freeman and Watts 1942 1943; Rylander 1948; Tow 1955). Even with mild and subtle frontal lobe damage, patients may seem to take hours to get dressed, to finish their business in the bathroom, or to shop and purchase simple items. For example, patients may spend hours in the bathtub playing with the bubbles. A curious mixture of obsessive compulsiveness and passive aggressiveness may be suggested by their behavior.

In severe cases, compulsive utilization of utensils and tools may occur, as well as distractability and perserveration. For example, following frontal lobotomy, "sometimes a pencil and a piece of paper will be enough to start an endless letter that may end up with the mechanical repitition of a certain phrase, line after line and even page after page" (Freeman and Watts 1943, p. 801).

Even with "mild" to moderate frontal lobe injuries patients may initially demonstrate periods of tangentiality, grandiosity, irresponsibility, laziness, hyperexcitability, promiscuity, silliness, childishness, lability, personal untidiness and dirtiness, poor judgment, irritability, fatuous jocularity, and tendencies to spend funds extravagantly. Unconcern about consequences, tactlessness, and changes in sex drive and even hunger and appetite (usually accompanied by weight gain) may occur, coupled with a reduction in the ability to produce original or imaginative thinking.

"Id rather have a bottle in front of me, than a frontal lobotomy" --anonymous

In some respects, damage to the frontal lobes, the right frontal and orbital frontal in particular, can create symptoms similar to a state of alcohol intoxication. This is because alcohol, which is a central nervous system depressant, knocks out and depresses the functioning of the frontal lobes which serve as the senior executive of the brain and personality. If the "senior executive" gets drunk, executive and inhibitory control over the rest of the brain will be impaired.

However, the initial disinhibitory stages of acute intoxication are generally followed by a drunken stupor; the drunk becomes pacified, lethargic, apathetic, and may pay pass out. These symptoms may also result from frontal lobe damage; and some patients may fluctuate between these extremes.

The effects of brain damage on behavior was noted by the ancients and was practiced by physicians even during the middle ages as a means of controlling the behavior of the insane.

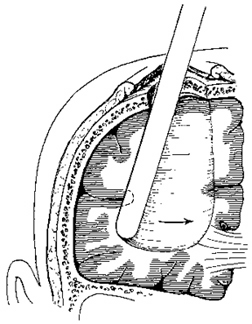

Frontal lobotomy, also known as psychosurgery, was born in 1890, precisely because frontal lobe damage can induce apathy. It was in that year that psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt crudely destroyed frontal lobe tissue of six extremely agitated and often violent patients in a psychiatric hospital in Switzerland. Half of these patients became stuporous and were completely pacified. Burckhardt claimed a 50% success rate. However, the other 50% became little different from a wide-awake and violent drunk.

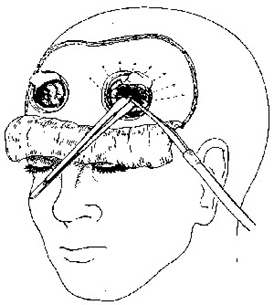

in 1935, a Portuguese physician Ant�nio Egas Moniz drilled holes into the heads of patients and stuck a sharp wire loop into the patient's head and destroyed varying amounts of frontal lobe tissue. He called his surgical technique, "prefrontal leucotomy." Moniz was given the Nobel Prize for medicine in 1949 for this butchery.

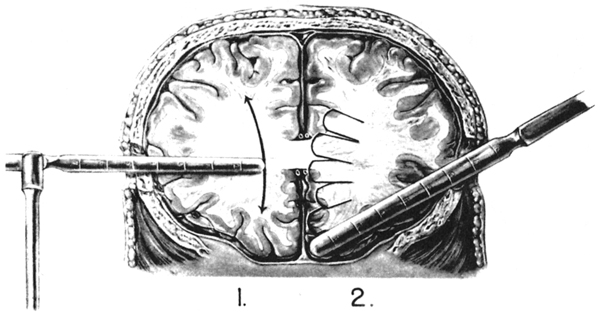

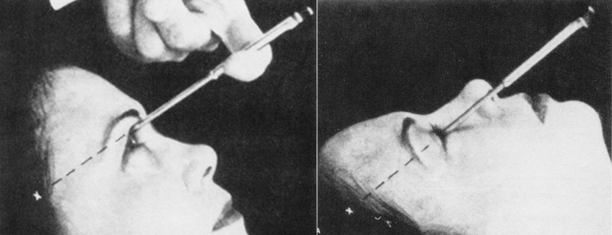

In 1936, Walter Freeman and James Watts developed the surgical ice pick approach, which essentially consisted of sticking a blade into a patient's brain and going "swish swish swish." They called this the "precision method." Most of Freeman's patients were made much worse by the procedure, and Freeman and Watt's took a surprisingly jocular view of these successes:

As stated by Freeman and Watts (1943, p. 805): "Sometimes the wife has to put up with some exaggerated attention on the part of her husband, even at inconvenient times and under circumstances which she may find embarrassing. Refusal, however, has led to one savage beating that we know of, and to an additional separation or two" (p. 805).

Curiously, in these situations Freeman and Watts (1943, p. 805) have suggested that "spirited physical self-defense is probably the best strategy of the woman. Her husband may have regressed to the cave-man level, and she owes it to him to be responsive at the cave-women level. It may not be agreeable at first, but she will soon find it exhilarating if unconventional."

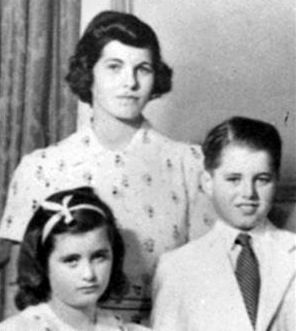

Rosemary Kennedy, the sister of president John F. Kennedy and senator Robert Kennedy, was born mildly retarded. She did not always behave with the class and decorum expected of a Kennedy, and suffered mood swings. Dr. Freeman promised the Kennedy family he could cure her. At age 23, Rosemary was strapped to a table, her head immobilized, and while fully conscious Freeman proceeded to destroy her frontal lobes. He asked her to count and to recite prayers during the procedure and Freeman stopped cutting only after she no longer made any sense. She was "cured" he declared, and in fact, she no longer suffered mood swings. She became little more than a vegetable, unable to speak coherently, or control her bowels, or attend to her most basic needs. She died in a mental institution in 2005.

Following lobotomy or massive or even mild frontal injuries patients may become emotionally labile, irritable, euphoric, aggressive, and quick to anger, and yet be unable to maintain a grudge or a stable mood state as they rapidly oscillate between emotions (Bradford 1950; Greenblatt 1950; Joseph 2007a, 2011a; Rylander 1939; Strom-Olsen 1946; Stuss 1991; Stuss and Benson 2007). Depending on the degree of damage, they may become unrestrained, overtalkative, and tactless, saying whatever "pops into their head", with little or no concern as to the effect their behavior has on others or what personal consequences may result (Broffman 1950; Bogousslavasky et al. 1988; Freeman and Watts 1943; Joseph 2007a, 2011a; Luria 1980; Miller et al. 2007; Partridge 1950; Rylander 1939, 1948; Strom-Olsen 1946).

With severe injuries patients may seem inordinantly disinhibited and influenced by the immediacy of a situation, buying things they cannot afford, lending money when they themselves are in need, and acting and speaking "without thinking." Seeing someone who is obese they may call out in a friendly manner, "Hey, fatty", and comment on their presumed eating habits. If they enter a room and detect a faint odor, its: "Hey, who farted?"

Following severe injuries there may be periods of gross disinhibition which may consist of loud, boisterous, and grandiose speech, singing, yelling, and beating on trays. The destruction of furniture and the tearing of clothes is not uncommon. Some patients may impulsively strike doctors, nurses, or relatives and thus behave in a thoroughly labile, aggressive, callous and irresponsible manner (Benson and Geschwind 1971; Freeman and Watts 1942, 1943; Joseph 2007a, 2011a; Strom-Olsen 1946; Stuss and Benson 2007).

One patient, with a tumor involving the right frontal area, following resection, attempted to throw a fellow patient's radio through the window because he did not like the music. He also loudly sang opera in the halls. Indeed, during the course of his examination he would frequently sing his answers to various questions (Joseph 2007a).

Impulsiveness can also be quite subtle. Luria (1980, p. 294), describes one patient with a slowly growing frontal tumor "whose first manifestation of illness occurred when, on going to the train station, he got into the train which happened to arrive first, although it was going in the opposite direction."

UNCONTROLLED LAUGHTER AND MIRTH

Frontal lobe patients can act in a very childish and puerile manner, laughing at the most trivial of things, making inappropriate jokes, teasing, and engaging total strangers in hillarious conversation (Ackerley 1935; Freeman and Watts 1942, 1943; Kramer 1954; Luria 1980; Petrie 1952; Rylander 1939, 1948; Stuss and Benson 2007). Pathological laughter, joking, and punning may occur superimposed upon a labile effect. Many are vastly amused by their own jokes (Ironside 1956; Kramer 1954; Martin 1950). They can be quite funny, but often they are not!

In part, frontal lobe humor is a function of tangentiality and disinhibition. Loosely connected ideas are strung together in an unusual fashion. The tendency to exaggerate and to impulsively comment upon whatever draws their attention is also contributory, and their humor and laughter may have a contagious quality.

Nevertheless, rather than funny, frontal patients may seem crude and inappropriate. They may laugh without reason and with no accompanying feelings of mirth. These disturbances were in fact documented over 50 years ago. Kramer (1954) for example, describes 4 cases of uncontrollable laughter after lobotomy. They were unable to stop their laughter on command or upon their own volition. The laughter would come on like spells, occurring up to a dozen times a day, and/or continue into the night, requiring sedation in some cases. In these instances, however, the laughter had no contagious aspects but seemed shrill and "frozen." When questioned about the laughter the patients either confabulated a reason for their mirth, or seemed completely perplexed as to the cause.

In general, right orbital damage seems to result in the most severe alterations in mood and emotional functioning (Grafman et al. 2007), which in turn is likely a function of the greater role of the right frontal lobe and the right hemisphere including the right inferior frontal lobe, in the regulation of emotion and arousal (Joseph, 2007a, 1988a, 2011a; Konishi et al., 2011; Tucker, 1981).

In addition to laughter, punning and "Witzelsucht" (puerility), language might become excessively and inappropriately profane, and the patient may seem inordinately inconsiderate, outspoken, and obstinant (Broffman 1950; Partridge 1950; Strom-Olsen 1944; Stuss 1991; Stuss and Benson 2007). However, although they may easily swear, laugh, joke, and make threats, they may also become inordinately apathetic and listless, spending much of their time doing nothing.

Frontal lobe damage and lobotomy reduces one's ability to profit from experience, to anticipate consequences, or to learn from errors (Bianchi 1922; Drewe 1974; Goldstein1944; Halstead 1947; Milner 1964 1971; Nichols and Hunt 1940; Joseph 2007a, 2011a; Petrie 1952, Porteus and Peters 1947; Rylander 1939; Shallice and Burgess 1991; Stuss and Benson 2007; Tow 1955). There is a reduction in creativity, fantasy, dreaming, and abstract reasoning. The capacity to synthesize ideas into concepts or to grasp situations in their entirety is lost, and interests of an intellectual nature are diminished, or sometimes abolished. As described by Freeman and Watts (1943, p. 803) "patients who were great readers of good literature will be interested only in comic books or movie magazines. Men of considerable intellectual achievement... when discussion turns on the great events of the day will pass off some cliches as their own opinions".

In mild or severe cases thinking may be contaminated by perseverative intrusions of irrelevant and tangential ideas, randomly formed associations, and illogical intellectual activity. These patient are also often effected by the immediacy of their environment and have difficulty making plans or adequately meeting long term goals. Even if highly intelligent, they may no longer be able to use that intelligence affectively, and they may undergo a complete personality change.

In 1981, following his graduation from Stanford University, D.F., and three friends, founded their own electronics/computer company, which immediately became a modest success, and began to rapidly grow and expand. D.F., tall, lanky, clumsy, already losing his hair, and only 27 years old, was an electronics genius and in all respects the classic "nerd." He had never dated, and never had a social life, and throughout his younger years had been treated like a "retard" by his school mates. Although he was "vice president" of his company, and a co-owner, and worth over seven figures, he simply lacked the self-confidence to mingle or socialize with the opposite sex, and didn't feel comfortable interacting with anyone who did not share his enthusiasm for computers. Neverthless, D.F. was lonely. He needed a girlfriend.

In 1985 his company "went public" (made a public offering of stock) and D.F. was suddenly a multi-millionaire without a girlfriend. It was soon thereafter that a "new girl" was hired to work as an assistant and secretary, just outside his office. "She was beautiful! An angel! Long blond hair. Green eyes. She must have weighed only 100 pounds. Everytime I walked out side my office I felt shocked to see her. And she wasn't married. She was only 23. I started thinking about her all the time. I coudn't concentrate. I dreamed about her. I wanted to marry her. I loved her. Love her!" he gushed, his words racing.

But D.F. didn't have the nerve to approach her, or talk to her, except to say hi. "She always smiled at me, when I said hi. A big smile. I knew she liked me." But he still didn't ask her out. Instead, he began to fantasize, about being married, having children.

And then after several tortured months, D.F. came to a decision. "I bought her a huge diamond ring. Ten thousand dollars. And I asked her to marry me."

According to D.F., he simply approacher her, offered her the ring, which she took and put on her finger. And then he asked her to marry him. Apparently she was stunned. Apparently she even laughed. Apparently she even thanked him for the ring. But she said no.

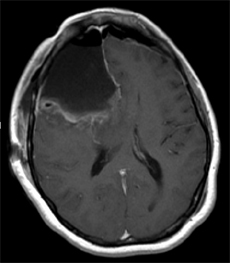

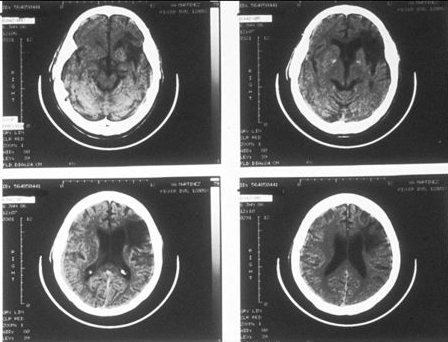

D.F. was mortified and became massively depressed. He couldn't function. Couldn't think."I just wanted to die." D.F. purchased a handgun. Took it home. Placed the barrel in his mouth. But then aimed it incorrectly. He pointed it directly into the roof of his mouth, pulled the trigger, and then blew out his right frontal lobe.

Approximately six months later, D.F. arrived for his appointment to see me, with a toothbrush, toothpaste, hair brush, and wash rag sticking out of his shirt pocket (Joseph 1988a). When I asked, pointing at his pocket, "What's all that for?" he replied with a laugh, "That's just in case I want to brush my teeth," and in so saying he quickly drew the toothbrush from his pocket and began to demonstrate. During the course of the exam he laughingly demonstrated how the skin flap which covered the hole in his head (from the craniotomy and bullet wound) could bulge in or out when he held his breath or held his head upside down. He even climbed up and stood on this examiner's desk and bent over so as to offer a better view of the hole in his head.

Throughout the exam he behaved in a silly, puerile manner, often joking and laughing inappropriately. Even when discussing the blond secretary and the aftermath, he laughed, becoming serious for only a few moment when I asked him if she had given him back the ring. She hadn't. Nevertheless, despite his bizarre and inappropriate behavior, D.F.'s overall WAIS-R IQ was above 130 (98% rank: "Very Superior"). Unfortunately, although he had a high IQ, he could no longer employ that intelligence, intelligently. On the other hand, he was no longer depressed, which is one of the many reasons that frontal lobotomies became such a popular in-office psychiatric procedure during the 1940s and 1950s.

Frontal lobe patients also may have difficulty thinking up or considering alternative problem solving strategies and thus developing alternative lines of reasoning. For example, Nichols and Hunt (1940) dealt a patient five cards down including the ace of spades which always fell to the right on two successive deals and then to the left for two trials. The patients task was to learn this pattern and turn up the ace. The patient failed to master this after 200 trials.

Some frontal lobe patients may also have extreme difficulty sorting even common everyday objects according to category (Rylander, 1939; Tow, 1955), for example, sorting and grouping drinking containers (glasses) with other drinking containers (mugs), tools with tools, etc. Similarily, they may have difficulty performing the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (Crockett et al., 2007; Drewe, 1974; Milner, 1964, 1971) which involves sorting geometric figures according to similarity in color, shape, or number. However, the manner in which a patient fails on this task is dependent on the locus and laterality of the damage.

For example, patients with orbital damage seem to have relatively little difficulty performing this category sorting task (Drewe, 1974; Milner, 1971). Similarly, patients with right frontal damage, although they show a tendency to make perseverative type errors (i.e. persisting in a choice pattern which is clearly indicated as incorrect), perform significantly better than those with left frontal damage (Drewe, 1974; Milner, 1964, 1971). Thus overall, patients with left medial and convexity lesions perform most poorly, and have the greatest degree of difficulty thinking in a flexible manner or developing alternative response strategies.

I.Q. Testing

A number of studies of conceptual functioning have been performed before and after surgical destruction of the frontal lobes. Although in some cases, such as D.F., described above, the IQ remains high, performance is so uneven and there is so much intertest variability that it is apparent that patients have suffered significant declines (Petrie, 1952; Smith, 1966). In studies in which patients undergoing frontal leucotomy for intractable pain were administered the Wechsler Intelligence Scales both pre- and post surgery, a 20 point drop in the IQ was reported (Koskoff, 1948, cited by Tow, 1955).

Likewise, in cases where the Raven's Progressive Matrices or Porteus Mazes were administered both before and after lobotomy, significant declines in intellectual functioning have been documented (Petrie, 1952; Porteus & Peters, 1947; Tow, 1955). As with most tests, the usual pattern is to improve with practice. Hence, these results (and those mentioned above) indicate that frontal lobe damage disrupts abstract reasoning skills, verbal-nonverbal pattern analysis, learning and intellectual ability, as well as the capacity to anticipate the consequences of one's actions or to profit from experience. However, the effects of frontal damage on IQ is dependent on the locus of the damage.

For example, left frontal patients show lower Wechsler IQs than those with right frontal lesions (Petrie, 1952; Smith, 1966). In fact, 17 of 18 patients with left frontal damage reported by Smith (1966) scored lower across all subtests compared to those with right frontal lesions. Indeed, patients with left sided destruction perform as poorly as those with bilateral damage (Petrie, 1952).

In analyzing subtest performance, Smith (1966) notes that left frontal lobotomy patients scored particularly poorly on Picture Completion (which requires identification of missing details). This is presumably a consequence of the left cerebral hemisphere being more conerned with the perception of details (or parts, segments) vs wholes (chapters 10, 11). Petrie (1952), however, reports that performance on the Comprehension subtests (i.e. judgment, common sense) was most significantly impaired among left frontals.

In contrast, individuals with severe right frontal damage have difficulty performing Picture Arrangement--often leaving the cards in the same order in which they are laid (McFie & Thompson, 1972). This may be a consequence of deficiencies in the capacity to discern social-emotional nuances, a function at which the right hemisphere excels (chapter 10).

Nevertheless, since so few studies have been conducted it is probably not reasonable to assume that lesions lateralized to the right or left frontal lobe will always effect performance on certain subtests, particularly if there is a mild injury. It is also important to consider in what manner lateralized effects on IQ may be contributing to or secondary to reduced motivation and apathy since bilateral and left frontal damage often give rise to this constellation of symptoms. If the patient is apathetic they are not going to be motivated to perform at the best of their ability.

Thus, where with left frontal injuries patients may seem apathetic, indifferent, and/or severely depressed and psychotic if not schizophrenic, right frontal injuries are associated with manic-like disinhibited states, including waxing and waning abnormalities associated with manic-depression. Patient's may become so disinhibited they develop the classic "frontal lobe personality," and become disinhibited, hyperactive, euphoric, extroverted, labile, overtalkative, and may develop perseveratory tendencies. Patients may become so disinhibited, delusional, grandiose, and emotionally labile that they develop what has classically been described as mania.

By contrast, with a left frontal lesion, rather than a loss of emotional control, there is a loss of emotion, and the patient will become severely apathetic, indifferent, and with massive lesions unresponsive, though classically left frontal injuries are associated with depression.

These right and left frontal differences are a function of lateralized differences in the control over arousal. Whereas the orbital frontal lobes contral limbic arousal, the right and left frontal lobes contraol neocortical arousal, with the right frontal lobe exerting bilateral inhibitory and excitatory influences, whereas the left frontal lobe exerts unilateral excitatory influences.

DISINHIBITED SEXUALITY

In some cases following frontal lobe damage patients may engage in inappropriate sexual activity (Benson and Geschwind 1971; Brutkowski 1965; Freeman and Watts 1942, 1943; Girgis 1971; Leutmezer et al., 2011; Lishman 1973; Miller et al. 2007; Strom-Olsen 1946; Stuss and Benson 2007). One patient, after a right frontal injury began patronizing up to 4 prostitutes a day, whereas his premorbid sexual activity had been limited to Tuesday evenings with his wife of 20 years (Joseph 1988a).

Another patient with a right frontal stroke propositioned nurses and would spontaneously reach out and fondle large breasted women (Joseph 1988a).

It is not unusual for a hypersexual, disinhibited frontal lobe injured individual to employ force. One individual who was described as quite gentle and sensitive prior to his injury, subsequently raped and brutalized several women. Similar behavior has been described following lobotomy.

Seizure activity arising from the deep frontal regions have also been associated with increased sexual behavior, including sexual automatisms, exhibitionism, gential manipulation, and masturbation (Leutmezer et al., 2011; Spencer, Spencer, Williamson, & Mattson 2003; Williamson, et al., 1985). One young man that I evaluated and who was subsequently found, with depth electrode recording, to have seizures emitting from the right frontal lobe, had been arrested over 7 times for exposing himself in public. His parents complained that he would sometimes walk around the house grabbing and exposing his genitals, and would sometimes even pee on the floor. In fact, while I was evaluating him as he lay in bed at the Yale Seizure Unit (VAMC) he suffered a seizure which involved the following sequence. He grunted loudly and his left arm shot out in a lateral arc. His left hand then returned to his body and he began to fiddle with the buttons of his pajamas continuing in a downward motion until he reached his penis which he then took in his hand and began to squeeze. As I looked on, he suddenly began to urinate and with such force that I was nearly sprayed with urine. Fortunately, I deftly escaped by leaping to the side and against the wall which put me well out of his range.

By contrast, a young woman I examined with right frontal-temporal seizures would spread her legs and engage in pelvic thrusting, coupled with grunting, lip licking and tongue protrusion. Currier et al., (1971), have also reported pelvic thrusting and moaning, and sex appropriate vocalizations, with temporal lobe seizures.

However, according to Leutmezer et al., (2011) and as based on prolonged scalp-EEG monitoring, sexual automatisms, such as "sexual hypermotoric pelvic or truncal movements are common in frontal lobe seizures," whereas "discrete genital automatisms, like fondling and grabbing the genitals are more common in seizures involving the temporal lobe." Presumably, the results of Leutmezer et al., (2011) differ from that of Currier, et al., (1971), Joseph (1988a, 2011a), Spencer et al., (2003), and Williams et al., (1985), due to their use of scalp rather depth electrodes which are more sensitive and exacting. On the other hand, temporal lobe/hippocampal sclerosis and atrophy were also documented in the Leutmezer et al. (2011) study.

Nevertheless, given the close functional association between the frontal and temporal lobes, and the fact that even a frontal seizure can propagate to the amygdala and thus involve the temporal lobe, perhaps the dysfunctional differences in abnormal sexual behavior are due to seizure origin and the subsequent spread of seizure activity.

There is also some evidence for functional laterality in regard to sexual automatisms and abnormal sexual behavior. In most instances, "sexual" seizures are associated with right frontal seizure foci (Joseph 1988a; Spencer et al. 2003). However, patients may also become hyposexual (Greenblatt 1950; Miller et al. 2007), especially with left frontal injuries, and/or experience genital pain with left temporal seizures (Leutmezer et al., 2011).

Mania and manic-like features have been reported in many patients with injuries, tumors, and even seizures involving predominantly the frontal lobe and/or the right hemisphere (Bogousslavsky et al. 1988; Clark and Davison 1987; Cohen and Niska 1980; Cummings and Mendez 1984; Forrest 1982; Girgis 1971; Jack et al. 2003; Jamieson and Wells 1979; Joseph 2007a, 1988a, 2011a; Lishman 1973; Miller et al. 2007; Oppler 1950; Robinson and Downhill 2013; Rosenbaum and Berry 1975; Starkstein et al. 1987; Stern and Dancy 1942).

One frontal patient described as formerly very stable, and a happily married family man, became excessively talkative, restless, grossly disinhibited, sexually preoccupied, extravagantly spent money and recklessly purchased a business which soon went bankrupt (Lishman 1973).

In another case, a 46-year old woman was admitted to the hospital and observed to be careless about her person and room, and incontinent of urine and feces. She slept very little and acted in a hypersexual manner. Her symptoms had developed several months earlier when she began accusing a neighbor of taking things she had misplaced. She also would confront him and strip off her clothes. She began going about in just a slip and bra, and informed people she was descended from queens, was fabulously wealthy, and that many men wanted to divorce their wives and marry her. During her hospitalization she was frequently quite loud, disoriented to time and place, and extremely tangential, jumping from subject to subject. After several years she died and a meningioma involving the orbital surface of the right frontal lobes was discovered (Girgis 1971).

I have examined 19 male and five female patients who developed mania after suffering a right frontal stroke or trauma to the right frontal lobe. All but four of the males had good premorbid histories and had worked steadily at the same job for over 3-5 years (e.g. Joseph, 2007a, 1988a). Following their injuries all developed delusions of grandeur, pressured speech, flight of ideas, decreased need for sleep, indiscriminant financial activity or irresponsibility, emotional lability, and increased libido, including, in one case, persistent sexual overtures coupled with genital exposure, to the patient's sisters and mother.

One formerly very conservative engineer with over 20 patents to his name suffered a right frontal injury when he fell from a ladder. He became sexually indiscriminate and reportedly patronized up to 3 prostitutes a day, whereas before his injury his sexual activity was limited to once weekly with his wife. He also spent money lavishly, suffered delusions of grandeur, camped out at Disney Land and attempted to convince personnel to fund his ideas for a theme park on top of a mountain, and at night had dreams where the Kennedy's would appear and offer him advice --and he was a republican!

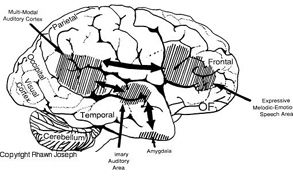

Although language is usually discussed in regard to grammar and vocabulary, it is also emotional, melodic and prosodic --features which enable a speaker to convey and a listener determine, intent, attitude, feeling and meaning (chapters 10, 15). A listener comprehends noy only what is said, but how it is said--what a speaker feels.

Feeling and attitude are conveyed through the melody (musical qualities), inflection, intonation, and prosody of one's voice, and by varying the pitch, inflection, timbre, stress contours, melody, as well as the rate and amplitude of speech --capacities predominantly mediated by the right half of the cerebrum (see chapter 10).

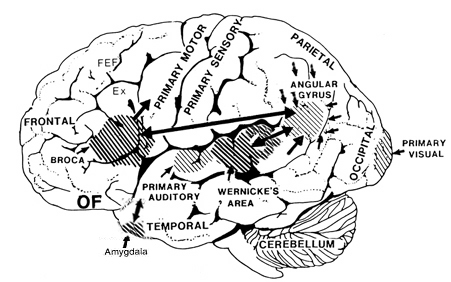

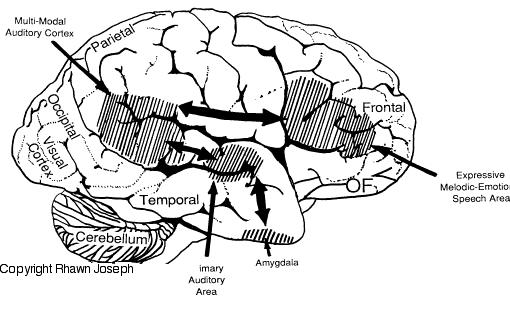

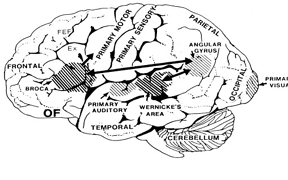

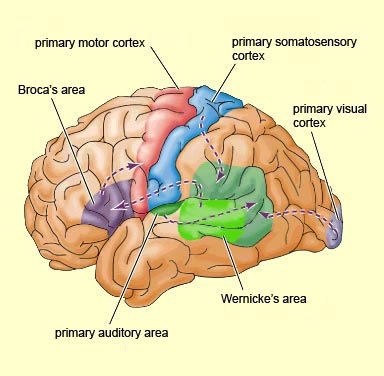

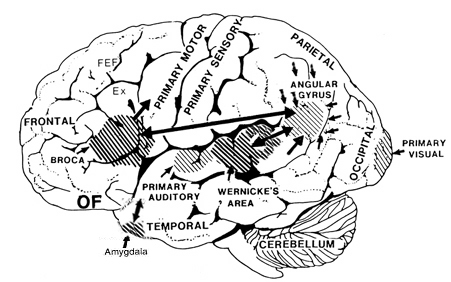

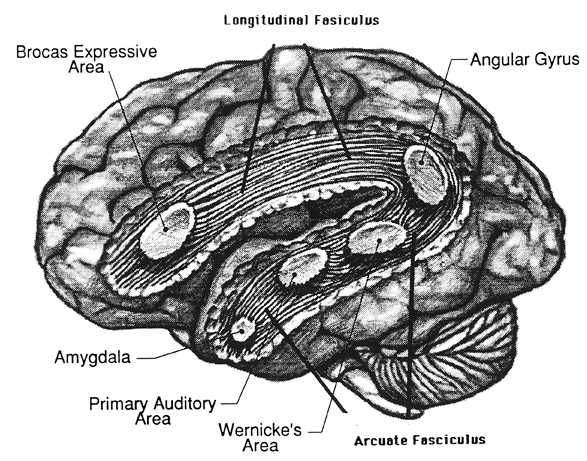

Patients with severe forms of Broca's expressive aphasia are unable to discourse fluently. However, they may be capable of swearing, making statements of self-pity, praying, singing, and even learning new songs (Gardner 1975; Goldstein 1942; Gorelick and Ross 1987; Joseph 1988a; Ross 1981; Smith 1966; Smith and Burklund 1966; Yamadori, Osumi, Mashuara, and Okuto, 1977)--although in the absence of music they would be unable to say the very words they had just sung. This is because the ability to produce non-linguistic and musical/emotional sounds is mediated by the undamaged right frontal lobe and limbic nuclei (Gardner 1975; Gorelick and Ross 1987; Joseph 1988a; Ross 1993; Shapiro and Danly 1985). Indeed, just as the left frontal convexity (i.e. Broca's area) subserves the syntactical, temporal-sequential, motoric, and grammatical aspects of linguistic expression (Foerster 1936; Fox 2013; Goodglass & Kaplan, 2000; LeBlanc 1992; Petersen et al. 1988, 1989; Sarno, 1998), there is a homologous region within the right frontal area which mediates the expression of emotional and melodic speech (Gorelick and Ross 1987; Joseph 1982, 1988a, 2011a; Ross 1981, 1993; Shapiro and Danly 1985).

With massive damage involving the right frontal melodic-emotional speech area, speech may become flat and monotonous, or conversely, the ability to alter or convey melodic and prosodic elements may become exceedingly abnormal and distorted. With extensive injuries to the right frontal lobe, patients may lose control over their voice and at times may sound as if they are crying, wailing, or screeching. Such patients may loose the ability to engage in vocal mimicry or to accurately repeat various statements in an emotional manner (Gorelick and Ross 1987; Joseph 1988a; Ross 1981, 1993).

With mild damage, rather than severe distortions or a loss of melody, the intonational qualities of the voice can become mildly abnormal and patients may seem to be speaking with an odd midwestern-like accent--particularly with deep lesions of the right frontal area, perhaps involving the cingulate or basal ganglia. Prosodic distortion in the form of an unusual accent is sometimes seen in seizure disorders involving deep right frontal or frontal-temporal areas.

On the otherhand, with left frontal lesions some patients develop what sounds like an unlearned foreign accent, as if they were from Germany, France, etc. (Blumstein et al. 1987; Graff-Radford et al. 2007). This is due, in part, to distortions involving the pronounciation of vowells.

When damage is limited to this right frontal emotional-motor speech area, the ability to comprehend and understand prosodic-emotional nuances appears to be somewhat intact (Gorelick & Ross, 1987; Joseph, 1988a; Ross, 1993). However, with right temporal injuries, the ability to comprehend these nuances may be lost (Ross, 1993).

It is interesting to note, however, that despite the clinical, neuropsychological, and neuroanatomical evidence indicating that the right frontal and right temporal areas contribute to the production of emotional prosodic melodic speech, that functional imaging and blood flow studies have failed to display significant activity in these regions during language-related activities (Frost, et al., 2011; Pujol, et al., 2011)--a function perhaps, of the insensitivity of the tasks and/or measures employed in this regard.

One frontal patient when asked what he received for Christmas replied, "I got a record player and a sweater." (Looking down at his boots) "I also like boots, westerns, popcorn, peanuts and pretzels." Another right frontal patient when asked in what manner an orange and a banana were alike replied, "fruit. Fruitcakes--ha ha--tooty fruity." When asked how a lion and a dog were alike he responded, "They both like fruit--ha ha. No. That's not right. They like trees--fruit trees. Lions climb trees and dogs chase cats up trees, and they both have a bark."

Tangentiality is in some manner related to impulsiveness as well as circumlocution. In contrast, patients with circumlocutious speech often have disturbances involving the left cerebral hemisphere and frequently suffer from word finding difficulty and sometimes receptive or expressive dysphasia. They experience difficulty expressing a particular idea or describing some need as they have trouble finding the correct words. Thus talk around the central point and only through successive approximations are able to convey what they mean to say.

Patients with tangential speech lose the point altogether. Instead, words or statements trigger other words or statements which are related only in regard to sound (e.g. like a clang association) or some obscure and ever shifting semantic category. Speech may be rushed or pressured and the patient may seem to be free associating as they jump from topic to topic.

Hence, in contrast to the aphasia, or speech arrest associated with left frontal injuries, right frontal lesions may result in speech release ("motor mouth"). Speech becomes disinhibited, pressure, and contaminated with tangential associations, and the patient may seem to be free associating as they jump from topic to topic. In the extreme speech becomes filled with confabulatory ideas.

When secondary to right (or bilateral) frontal damage, speech may become exceedingly bizarre, delusional, and fantastical, as loosely associated ideas become organized and anchored around fragments of current experience.

For example, one patient, when asked as to why he had been hospitalized, denied that there was anything wrong, but instead claimed he was there to do some work. When asked what kind of work, he pointed to the air conditioning unit, and stated: "I'm a repair man. I'm here to fix the air conditioner. Now, if you'd please excuse me. I've got work to do."

A 24 year old store cleark who received a gunshot wound (during the course of a robbery) which resulted in destruction of the right inferior convexity and orbital areas, attributed his hospitalization to a plot by the government to steal his inventions (Joseph 2007a). He claimed he was a famous inventor, had earned millions of dollars and had even been on TV. When it was pointed out that he had undergone surgery for removal of bone fragments and the bullet, he pointed to his head and replied, "that's how they are stealing my ideas."

Another patient, formerly a janitor, who suffered a large right frontal subdural hematoma (which required evacuation) soon began claiming to be the owner of the business where he formerly worked (Joseph 1988a). He also alternatively claimed to be a congressman and fabulously wealthy. When asked about his work as a janitor he reported that as a congressman he had been working under cover for the C.I.A. Interestingly, this patient, also stated he realized what he was saying was probably not true. "And yet I feel it and believe it though I know it's not right."

Frontal lobe confabulation seems to be due to disinhibition, difficulties monitoring responses, withholding answers, utilizing external or internal cues to make corrections, accessing appropriate memories, maintaining a coherent line of reasoning, or suppressing the flow of tangential and circumstantial ideas (Fischer et al. 2013; Joseph 2007a,1988a, 2011a; Johnson, O'Connor and Cantor 2007; Kapur and Coughlan 1980; Shapiro et al.1981; Stuss et al. 1978; Stuss and Benson 2007). That is, since the right frontal lobe can no longer regulate information processing and the flow of perceptual and ideational activity, information that is normally filtered out and suppressed is instead expressed. In consequence, the Language Axis of the left hemisphere becomes overwhelmed and flooded by irrelevant, bizarre associations, leading sometimes to the expression of false memories, which the patient (that is, Broca's area) repeats (Joseph, 1982, 2007ab, 1988ab).

As noted, in some respects injuries involving the orbital frontal lobes can result in symptoms similar to those with right frontal injuries, including the production of confabulatory ideation. However, in contrast to right (or bilateral) frontal injuries which may result in the production of fantastical spontaneous confabulations where contradictory facts are ignored or simply incorporated, confabulatory responses associated with orbital injuries tend to be more restricted, transitory, and in some cases must be provoked (Fischer et al. 2013).

DEPRESSION, APATHY, APHASIA, SCHIZOPHRENIA

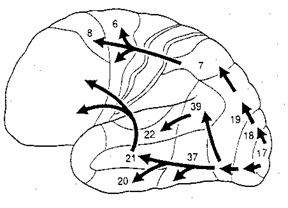

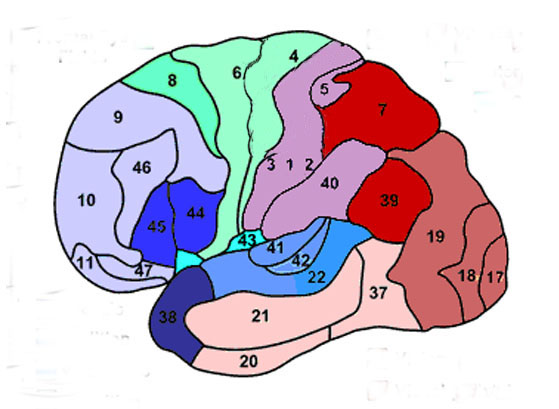

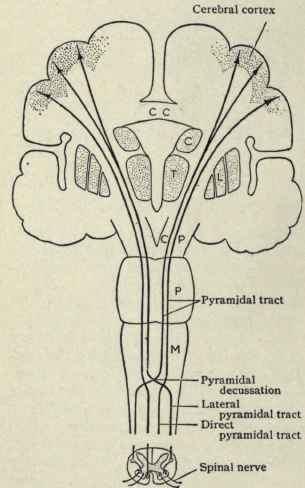

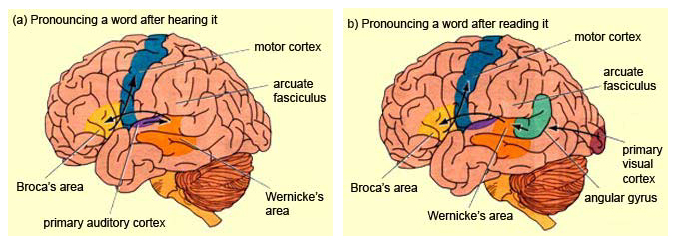

Broca's speech are is located in the general vicinity of the posterior- inferior region of the left frontal area (i.e. third frontal convolution), and includes portions of areas 45, 6, 4, and all of area 44. This region is multimodally responsive (Passingham, 2007) and receives projections from the auditory, visual, somesthetic areas (Geschwind, 1965; Jones & Powell, 1970), as well as massive input from the inferior parietal lobule and Wernicke's area via a rope of nerve fibers referred to as the arcuate fasciculus (which also links these areas to the amygdala). In addition, Broca's area receives fibers from and projects to the anterior cingulate as well as the brainstem periaqueductal gray which subserves vocalization.

Broca's speech area is a final converging destination point through which thought and other impluses come to receive their final sequential (syntactical, grammatical) inprint so as to become organized and expressed as temporally ordered motoric articulations; i.e. speech (Foerster 1936; Fox 2013; Goodglass, 1993; Goodglass & Kaplan, 2000; Kimura, 1993; LeBlanc 1992; Petersen et al. 1988, 1990; Sarno, 1998). Verbal communication, the writing of words (via transmission to Exner's area), and the expression of thought in linguistic form is made possible via Broca's area which programs the adjacent oral-laryngeal musculature as represented within the adjacent primary motor areas (Foerster 1936; Fox 2013; Kimura, 1993; LeBlanc 1992; Petersen et al. 1988, 1990; Sarno, 1998); and which transmits to Exner's writing area so that words may be written.

The importance of Broca's area and the left frontal lobe has also been demonstrated through functional imaging. For example, the left frontal lobe becomes activated during inner speech and subvocal articulation (Paulesu, et al., 1993; Demonet, et al., 2014). The left frontal lobe also becomes highly active when reading concrete and abstract words (Buchel et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 1988), and when engaged in semantic decision making tasks (Demb et al., 2013; Gabrielli et al., 2006). Moreover, activation increases as word length increases and in response to long and umfamiliar words (Price, 2007).

With injuries to Broca's area the individual loses the capacity to produce fluent speech (Goodglass, 1993; Goodglass & Kaplan, 2000; Sarno, 1998). Output becomes extremely labored, sparse, and difficult, and they may be unable to say even single words, such as "yes" or "no". Often, immediately following a large stroke patients are almost completely mute and suffer a paralysis of the upper right extremity as well as right facial weakness (since these areas are neuronally represented in the immediately adjacent area 4). Patients are also unable to write, read out loud or repeat simple words. Interestingly, it has been repeatedly noted that almost immediately following stroke some patients will announce "I can't talk", and then lapse into frustrated partial mutism.

With less severe forms of Broca's (also referred to as expressive, motor, nonfluent, verbal) aphasia, speech remains labored, agrammatical, fragmented, extremely limited to stereotyped phrases ("yes", "no", "shit", "fine") and contaminated with syntactic and paraphasic errors i.e. "orroble" for auto, "rutton" for button (Bastiaanse, 2013; Goodglass, 1993; Goodglass & Kaplan, 2011; Haarmann & Kolk 2014; Hofstede & Kolk 2014; Levine & Sweet, 1982, 2003; Sarno, 1998; Tramo et al. 1988). Writing remains severely effected, as are oral reading and repetition. Such patients also have mild difficulties with verbal perception and comprehension (Hebben, 2007; Maher et al. 2014; Tramo et al., 1988; Sarno, 1998; Tyler et al. 2013), including the ability to follow 3-step commands (Lura 1980). Commands to purse or smack the lips, lick, suck, or blow are often, but not always, poorly executed (DeRenzi et al. 1966; Kimura 1993); a condition referred to as bucal-facial apraxia. Non-speech oral movements are seldom significantly effected (Goodglass & Kaplan, 2011; Hecaen & Albert, 1978; Kimura 1993; Levine & Sweet, 2003).

With mild damage, patients may demonstrate severe confrontive naming and word finding difficulties (anomia), as well as possible right facial, hand, and arm weakness. Speech is often characterized by long pauses, misnaming, paraphasic disturbances and articulatory abnormalities (Goodglass, 1993; Goodglass & Kaplan, 2011; Sarno, 1998). Stammering and the omission of words may also be apparent. Similarly, electrical stimulation of this region results in speech arrest (Ojemann & Whitaker, 1978; Lesser et al., 1984) and can alter the ability to write and/or perform various oral-facial movements. It is noteworthy that even with anterior lesions or surgical frontal lobectomy sparing Broca's area a considerable impoverishment of spontaneous speech can result (Luria, 1980; Milner, 1971; Novoa & Ardila, 1987).

Disturbances involving grammar and syntax, and reductions in vocabulary and word fluency in both speech and writing have been observed with frontal lesions sparing Broca's area (Benson, 1967; Crockett, Bilsker, Hurwitz, & Kozak, 2007; Goodglass & Berko, 1960; Milner, 1964; Novoa & Ardila, 1987; Petrie, 1952; Samuels & Benson, 1979; Stuss, et al., 1998; Tow, 1955). In word fluency tests, however, simple verbal generation (e.g. all words starting with L) is usually more severely impaired than semantic naming, e.g. all animals which live in the jungle--which is presumably a function of semantic processing being more dependent on posterior language areas (Stuss et al., 1998).

DEPRESSION, APHASIA, & APATHY

Depression, "psycho-motor" retardation, apathy, irritability, and blunted mental functioning are associated with neocortical injuries of the left lateral and medial frontal lobe. When Broca's area has been injured, patients not only have difficulty with expressive speech (Bastiaanse 2013; Goodglass and Kaplan 2011; Haarmann and Kolk 2014; Hofstede and Kolk 2014; Sarno, 1998) but they typically become exceedingly frustrated, irritable, and depressed (Gainnoti 1972; Robinson and Benson 1981; Robinson and Szetela 1981; Robinson and Downhill 2006).

In large part, depression is common with Broca's aphasia as patients are painfully aware of their deficit (Gainotti 1972; Joseph, 1988a). Indeed those with the smallest frontal convexity lesions often become the most depressed (Robinson and Benson 1981). Depression in these cases appears to be a normal reaction and as such is mediated by undamaged tissue; i.e., the right hemisphere which is dominant for emotional expression and perception (e.g. Borod 1992; Cancelliere and Kertesz 1990; Freeman and Traugott 1993; Heilman and Bowers 2006; Joseph 1988a; Van Strien and Morpurgo 1992). That is, the right hemisphere being emotionally astute, reacts appropriately to the patient's condition and becomes depressed. If fact, with the exception of at least one study (Mayberg et al., 2011) almost all other studies demonstrate increased right frontal activity in response to negative moods (Rauch et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2007, 2011; Teasdale et al., 2011) and decreased left frontal activity with depression (Bench et al., 2013). In fact, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the right frontal lobe reduces depressive symptoms (Klein et al., 2011), whereas left frontal activity increase with the alleviation of depression as demonstrated through functional imaging studies (Bench et al., 2013).

Not only are left frontal injuries associated with tearfulness, irritability, and depression (where it is the right which may actually feel sad), but psychiatric patients classified as depressed, and normal individuals made to feel severely depressed, demonstrate insufficient left frontal activation and arousal (d'Elia and Perris 1973, Perris 1974; Tucker et al. 1981). For example, reduced bioelectric arousal over the left frontal region has been reported following depressive mood induction (Tucker et al. 1981). Similarly depressed mothers and depressed children show reduced left relative to right frontal activation (reviewed in Dawson 2014). With recovery from depression left hemisphere arousal returns to normal levels.

Likewise, Patients who are severely depressed have been shown to demonstrate insufficient activation and a significant lower integrated amplitude of the EEG evoked response over the left vs right frontal lobe (d'Elia and Perris 1973, Perris 1974). Based on EEG and clinical observation, d'Elia and Perris have argued that the involvement of the left hemisphere is proportional to the degree of depression. Moreover, with recovery the amplitude of the evoked response increases to normal left hemisphere levels. Functional imaging of depressed states indicates reduced activity in the left frontal lobe and anterior cingulate (Bench, et al,., 1992) and when these individuals ceased to be depressed, activity levels increases (Bench et al., 2013).

Left frontal lobe depression is therefore seen in those who are aphasic, and those whose depression has been long standing or even recently provoked. The more severe the depression, the greater is the reduction in left frontal functioning (whereas with mild transient sadness there might be a reduction in right frontal activity). Hence, with massive left frontal dysfunction, including even when Broca's area is spared, patient may become exceeding depressed, apathetic , hypoactive and indifferent (Robinson et al. 1984; Robinson and Szetela 1981; Sinyour, et al. 2007). However, with severe injuries, instead of worried or emotionally depressed, the patient instead is indifferent, uncaring, apathetic, and emotionally blunted (Blumer and Benson 1975; Freeman and Watts 1942, 1943; Girgis 1971; Hecaen 1964; Luria 1980; Passingham 1993; Stuss and Benson 2007; Strom-Olsen 1946). One patient who "prior to his accident requiring amputation of the left frontal pole, had been garrulous, enjoyed people, had many friends, was active in community affairs" and had "true charisma... became quiet and remote, spent most of his time sitting alone smoking, and was frequently incontinent of urine, and occasionally of stool. He remained unconcerned and was frequently found soaking wet, calmly sitting and smoking. When asked, he would deny illness" (Blumer and Benson 1975, p. 196).

Similarly, inertia and apathy usually imediately follow surgical destruction or injury of the frontal lobes, the left frontal lobes in particular (Hillbom 1951; Lishman 1968). "The previously busy housewife who has always been a dirt-chaser, and who has kept her fingers perpetually busy with darning, crocheting, knitting, and so on, sits with her hands in her lap watching the 'snails whiz by'. Like a child she must be told to wipe the dishes, to dust the sideboard, to sweep the porch" and even then the patient completes only half the task as there is no longer any interest or initiative (Freeman and Watts 1943, p. 803). In some cases the apathy is so profound that "whoever has charge of the patient will have to pull him out of bed, otherwise he may stay there all day. It is especially necessary since he won't get up voluntarily even to go to the toilet" (p. 802).

Depressive-like features, however, also seem to result with left anterior damage sparing Broca's area such as when the frontal pole (of either hemisphere is compromised (Robinson et al. 1984; Robinson & Szetela, 1981; Sinyour, et al. 2007). As described by Kennard (1939) monkeys with bilateral frontal lobe damage would sit with their head sunk between their shoulders, neither blinking or turning their heads in response to noise, threats or the presence of intruders; but would stare absently straight ahead with no facial expression. In a similar study, following massive frontal destruction a monkey who was formerly quite active and the dominant leader of his group became inactive, indifferently watched others, failed to respond emotionally, and seemed to have lost all interest and ability to engage in complex social behavior (Batuyev, 1969).

In his summary of two large scale frontal tumor studies Hecaen (1964) noted the majority seemed confused, disorganized, apathetic, hypoactive, and suffering from inertia and feelings of indifference.However, puerility was also common among these patients and many demonstrated decreased judgment with either total or partial unawareness of the environment.

In some, this initial state of inertia disappears, whereas in others it becomes a lasting or even progressively severe disturbance. "The previously busy housewife who has always been a dirt-chaser, and who has kept her fingers perpetually busy with darning, crocheting, knitting, and so on, sits with her hands in her lap watching the 'snails whiz by'. Like a child she must be told to wipe the dishes, to dust the sideboard, to sweep the porch" and even then the patient completes only half the task as there is no longer any interest or initiative (Freeman & Watts, 1943, p. 803).

In part, depression coupled with apathy secondary to frontal injuries is probably related to damage to the interconnections with the medial region, an area which when damaged induces hypokinetic and apathetic states (see below). However, these latter patients are not depressed, but rather severly apathetic, indifferent, hypoactive, and poorly motivated. When questioned, rather than worried or truly concerned about their condition the overall picture is that of confusion, disinterest, and blunted emotionality (Freeman & Watts, 1942: Hacaen, 1964) i.e. there is a lack of worrisome thoughts or depressive ideation.

Hence, in part, apathetic and depressive features may result from left frontal convexity and frontal pole damage due to a severance of fibers which link emotional impulses (such as those being transmitted via the orbital and medial region) with external sources of input or cognitive activity which are transmitted to the convexity (i.e. disconnection), impulses which are transmitted from the medial frontal lobes to the orbital, superior, and anterior frontal lobes. Through these interconnections, emotional impulses arising in the limbic system, can be transmitted through the medial frontal lobes to the lateral frontal lobes, where they then become ideas. Or conversely, neocortical cognitions may be transmitted from the lateral neocortical surface to the medial areas where they are integrated to again become emotional ideas.

It was the recognition that the frontal lobes acted as a bridge between emotion and idea which led to the wide scale use of frontal lobotomy; i.e. surgical destruction of inter-linking fibers --a technique, which when used in the 1940s and 1950s, often involved little more than blindly swishing a "surgical ice pick" inside somebody's brain!

Moreover, convexity lesions, like medial damage, may result in a disconnection not only between cognitive-perceptual and emotional activity, but would prevent limbic system output from reaching the motor areas such that emotional-motivational impulses are unable to become integrated with motor activities. The patient is thus motorically hypo-emotionally aroused (i.e. depressed), and appears to be demonstrating psychomotor retardation. Just as left frontal convexity motor damage can result in left sided apraxia (due to right hemisphere disconnection from left parietal temporal-sequential output), the reverse can also occur. That is, with left frontal damage, linguistic impulses not only fail to become expressed, but emotional output from the right hemisphere and limbic system fail to become integrated with linguistic-ideation (i.e. thought). Ideas no longer come to be assigned emotional significance. In the extreme the motivational impetus to even engage in thought production is cut-off.

As pertaining to laterality, left frontal (vs. right) lesions are associated with reductions in intellectual and conceptual capability which often leads to confusion and a reduced ability to appreciate and appropriately respond to the external or internal environment. In these instances, one possible consequence is apathy, indifference, hyporesponsiveness, and depressive-like symptoms.

On the otherhand, it is possible that among psychiatric patients and otherwise normal, albeit, depressed individuals, that the left frontal region appears relatively inactive because the right frontal area is preoccupied with being depressed; the right frontal region is excessively aroused (Teasdale, et al., 2011). That is, excessive right frontal arousal leads to massive left frontal inhibition; i.e., the bilateral arousal system of the right hemisphere inhibiting the left.